‘Cash Buck’

By Amy Richardson for Curve Magazine, Issue 13

Jimmy Johns was not impressed. Of all the Nigerian photographers that had assembled to see what this photographer had to teach the most senior staff of Internews, he was the most dimissive of all of this softly spoken white man.

It was perhaps not surprising that the large man - who looked not dissimilar to Mike Tyson, tribal face markings and all - was bemused by the prospect of being lectured to by a boy from Adelaide, Australia. After all, what could an outsider know of the trials of working in a country where photographers are looked upon with outright suspicion? Where if you choose that line of work, you’re guaranteed to be beaten at least once in your career?

When it came time for Jimmy Johns to introduce himself, he sat slumped in his chair, head resting on his hand, and waved the question on to the next person.

“I thought perhaps he was shy, so I encouraged him,” said Cash. “But then, instead of telling us about himself, he started with a tirade on the inequities within the press, the lack of support from editors to publish their shots, and what do I intend to do about this? It started a lively debate on the censoring of information in a country with predominately government owned media, and Jimmy John’s frustration was both at the media and the insult of having this foreign little boy teaching him”.

While conducting photographic workshops in developing countries often results in confronting situations, and throws up the odd cultural challenge, it’s only so long that Cash can be back in Australia before getting itchy feet. To date he’s travelled to Nigeria, Indonesia, East Timor and most recently, Palestine.

“Commercial photography work fulfils me only so much,” he says. “Personally, I need something with a little more purpose. It’s a Catch 22 however, as a majority of my trips are fully self funded. What I earn with my commercial ventures enables me to work in developing countries, teaching photography and shooting freelance.”

While initially studying to be a graphic designer, Cash abandoned these plans after getting his first taste of photography. “The moment I saw that image slowly appear on the paper in the developing tray, I was hooked,” he laughs. “My interest in graphic design wanned and I left uni at the end of second year to become a photographic assistant.”

Cash’s photographs are achingly beautiful, and reflect the respect and fascination he holds for his subjects, not to mention a deeper purpose. “I guess with both my art photography and photojournalism, I am aiming to inspire people,” he says. “Whether for change or just through showing the hidden beauty in things.”

“With people, [I look] for an expression, a gesture, something that tells a story – with objects and environments, the unnoticed.”

He thrives on his ability to pass on this knowledge to others through workshops he conducts in countries many others wouldn’t dare to visit. The impact of learning the ability to communicate through and artistic medium is something he relishes witnessing in the people he teaches.

Cash’s most recent endeavour, volunteering with an organisation called the Freedom Theatre in Palestine, is a case in point. There the children forced into the Jenin refugee camp by the Israeli – Palestine conflict are taught acting, painting, creative writing and photography.

With movement being heavily restricted due to curfews and checkpoints, and ongoing conflict causing increased school drop out rates, the children of Jenin have much to feel frustrated about. Those at the Freedom Theatre are attempting to teach ways to channel their passions down a less destructive avenue.

“Creativity is a great medium for kids to express themselves, especially in a situation like this where most of the kids would have seen and felt a lot of suffering and loss,” Cash explains. In a clip contained on the Theatre’s website, some of the child participants can be seen explaining what it means to them to be involved in such a project. One teenage boy declares that being on the stage makes him feel powerful, akin to ‘throwing a Molotov cocktail’.

Cash says that while it’s a statement that many of us simply can’t understand, “it is a reality for these kids born into the oppression they are.”

“I’m teaching photography to a group of 20 kids aged 13 and 17 – I’m hoping I can inspire them to use the camera as their weapon for change, instead of violence,” he says. “It’s idealistic, I know, but I do believe photography is a strong tool for social reform. It gives power to the powerless and knowledge to the ignorant.”

While at first glance it may seem airy-fairy to be instructing people in what is commonly seen as an art form when their daily lives are often a struggle for survival, photography’s societal role is much greater than simple aesthetic pleasure.

Given the low literacy levels in most developing countries and the fact that it is rare for universities in developing countries to instruct their journalists in photography, there’s a real need for images within the press that are strong in their story telling ability, according to Cash.

“Imagery is a powerful communication tool. It is imperative for other sources of communication, like radio and photography to fill the void and keep the community informed,” he says.

Playing a part in helping fulfil this requirement, coupled with the personal satisfaction that derives from the nurturing the artistic capabilities of others, is what drives Cash.

“The looks of joy on the photographers faces when they have pulled off a strong shot using one of the techniques I’ve taught them – it’s priceless,” he says. “You can see them physically stand taller.”

“In Nigeria, the role of the photographer is not seen as a respected one, as it offers little pay and no room for advancement. I can’t say we changed that view within the community, but we definitely empowered the photographers to view their role as an important one within the community and as an effective tool for social reform. I left them knowing they were inspired and empowered.”

His personal body of work has also flourished through his time in these far flung places. Cash is currently in the ‘design stage’ of a book that is the culmination of a year long project imag[in]e, had humble beginnings as a daily picture he would email to his close friends. Interest soon grew and Cash now has hundreds of people on his email list, most of whom he’s never met.

“Many people commented during the year that it would be great to see all the images together, hence the book was born,” Cash says. “It’s a mixture of art and photojournalism, depending on where I was at the time! When I’m in Australia, the images are generally on the arty side, when I’m overseas the images are documentary in nature.”

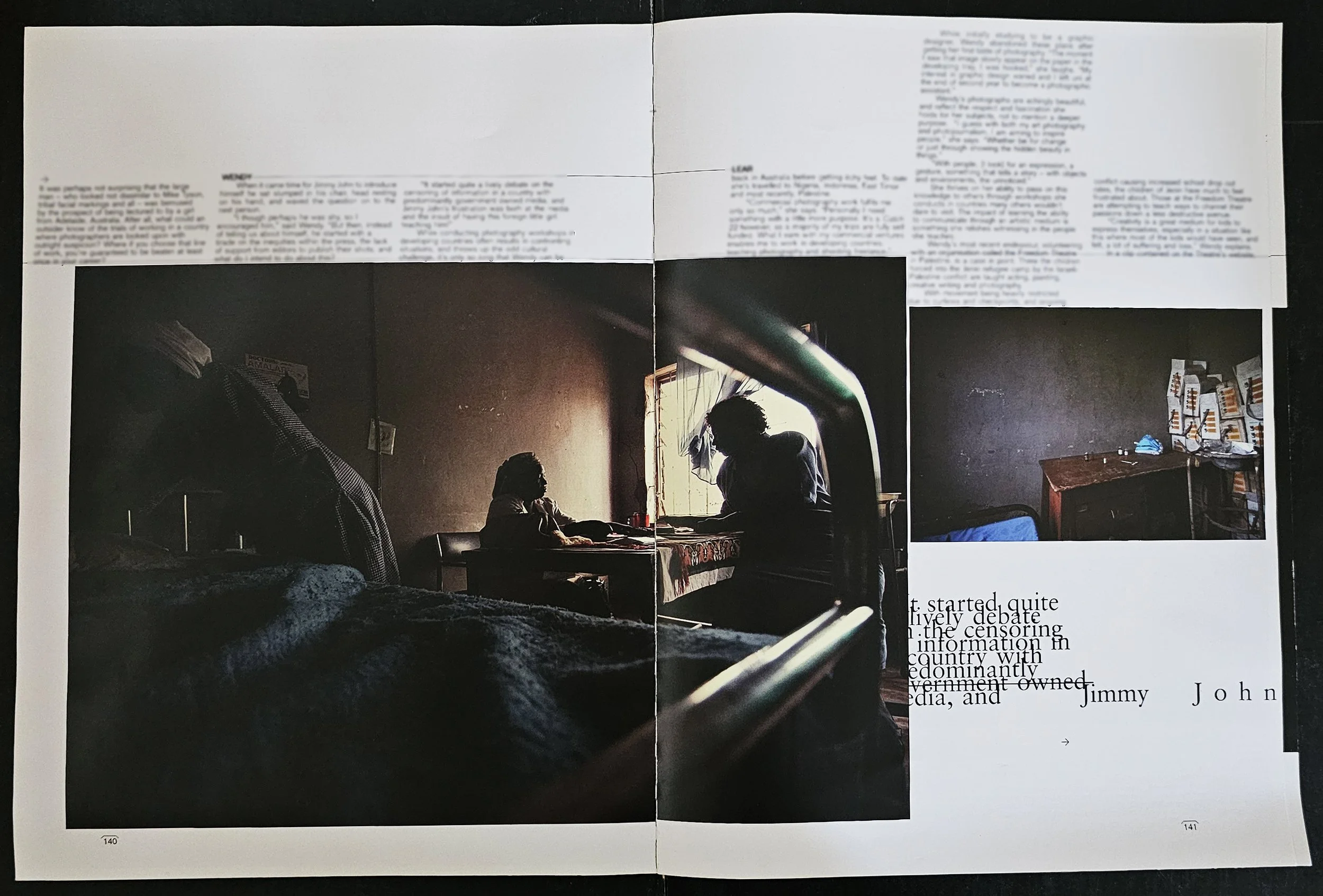

Much of the power of the images lie in their ability to impart the feeling that time and space have been compressed, and that the viewer has been transported to the scene. This may in part be credited to the painstaking care that Cash employs to win the confidence of his subjects.

“When I first arrive at a new place I go for days without shooting,” he explains.

“I spend time getting to know people and having them get to know and trust me, so that when I do start shooting, the images are ‘real’. I’m very conscious of ‘shoving’ my camera in peoples faces. I really try to respect people’s privacy which doesn’t always make for the best photojournalism, but I think I’m more suited to the photo essay structure whereby I spend considerable time with my subjects – they are comfortable with me and I with them. The real story unfolds.”

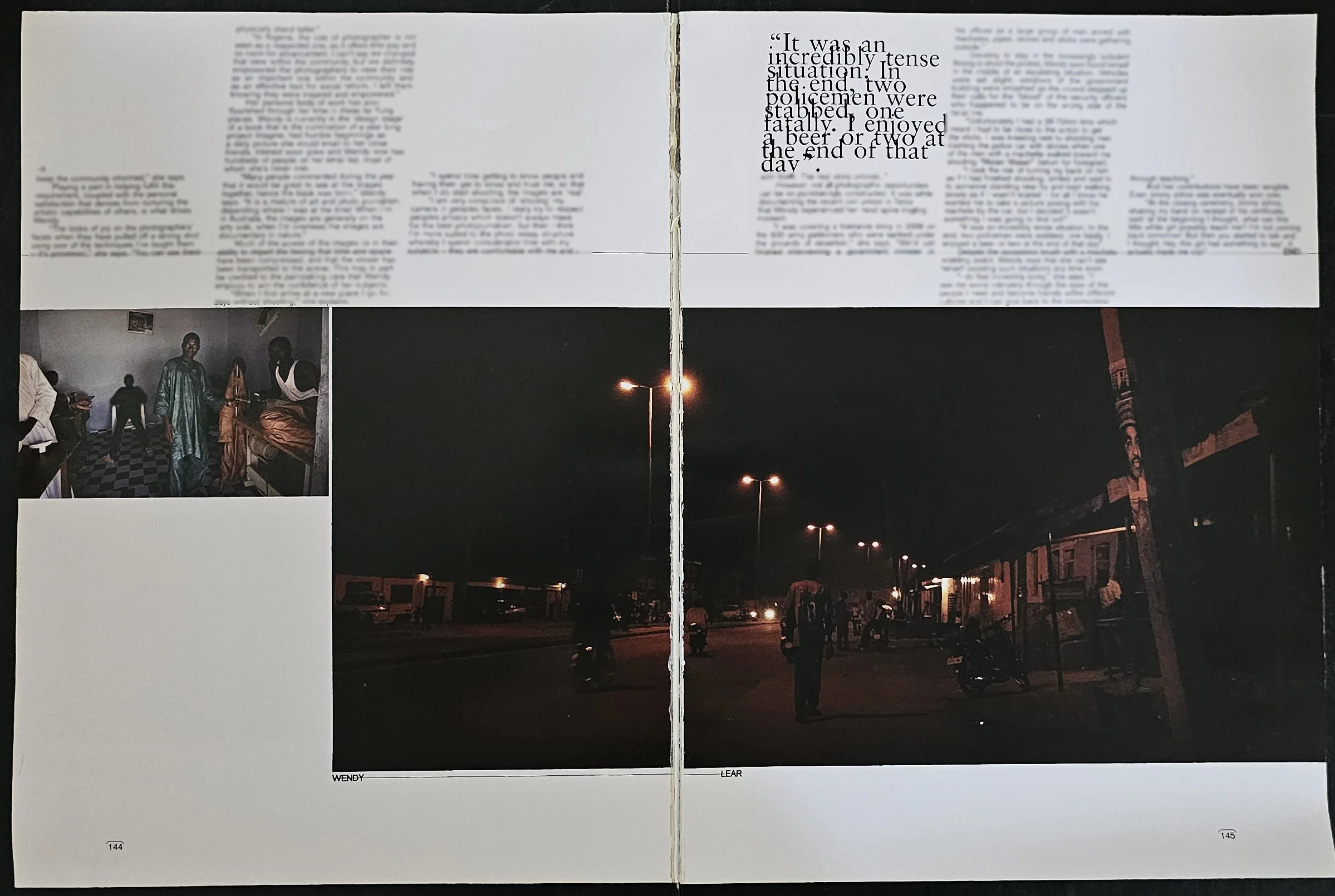

However, not all photographic opportunities can be so painstakingly constructed. It was while documenting the recent civil unrest in Timor that Cash experienced his most spine tingling moment.

“I was covering a freelance story in 2006 on the 600 army petitioners who were sacked under the grounds of desertion,” he says. “We’d just finished interviewing a government minister in his offices as a large group of men armed with machetes, pipes, stones and sticks were gathering outside.”

Deciding to stay in the increasingly turbulent throng to shoot the protest, Cash soon found himself in the middle of an escalating situation. Vehicles were set alight, windows smashed as the crowed stepped up their calls for the ‘blood’ of the security officers who happened to be on the wrong side of the racial line.

“Unfortunately I had a 28-70mm lens which meant I had to be close to the action to get the shots. I was kneeling, shooting men trashing the police car with stones when one of the men with a machete walked toward me shouting “Malae! Malae!” (Tetum for foreigner).

“I took the risk of turning my back on him as I had finished shooting, smiled and say hi to someone staying nearby and kept walking slowly as if I wasn’t scared – for all I know he wanted me to take his picture posing with his machete, but I decided it wasn’t something I wanted to find out!”

“It was an incredibly tense situation. In the end, two policemen were stabbed, one fatally.”

Despite the occasional brush with a machete wielding zealot, Cash says that he can’t see himself avoiding such situations any time soon.

“I do feel incredibly lucky,” he says. “I see the world intimately through the eyes of the people I meet and become friends with different cultures and I can give back to the communities through teaching.”

And his contributions have been tangible. Even Jimmy Johns was eventually won over.

“At the closing ceremony, Jimmy Johns, shaking my hand on the receipt of his certificate said ‘at the beginning I thought what can this little white boy teach me? I’m not coming back tomorrow! But then you started to talk and I thought, hey this boy has something to say’. It actually made me cry!”